City Pop, Escapism, and Nostalgia for the Future

Japanese city pop is back, but its revival isn’t only about posh romantic tunes—the genre’s popularity can be traced to our political mess and the need to escape it

This week's Night Water comes to us from friend-of-the-newsletter Matt Bucemi, who has graciously allowed me to republish his 2019 piece on city pop, a Japanese music genre that experienced a surge of internet-based popularity a few years ago. You can find more of Matt's writing on his website, including his most recent piece defending bad special effects and his musings on adaptation, particularly the seminal graphic novel Watchmen.

We’ve all stumbled on those YouTube videos for lo-fi beats to study to, featuring chilled-out tunes and inevitably accompanied by spiffy little animations of anime girls working away in their subtly futuristic bedrooms. Watch one of these, and you’ll very soon find yourself caught up in an endless number of Japanese city pop playlists—the modern taste in chill, airy electronic beats owes a great debt to city pop, which was a bright, icy-clean genre that flourished in Japan during the 1980s, the Bubble Era when anything seemed possible because the money was there to make it happen.

Japan’s Bubble Era wasn’t just a period of economic growth—it was among the fastest, biggest economic booms in human history. Japan was on track to becoming “the world’s greatest economic power”, fueled by technological innovations, cheap, reliable products, and high-value exports. In time, this boom era “caused the country’s standard of living to soar to among the highest in the world”, meaning that the “frugality and austerity that defined the country during the postwar era gave way to extravagance and conspicuous consumption.”

Someone had to make music for these rich-ass people. Music journalist Yutaka Kimura’s book Japanese City Pop Disc Collection defines city pop as “urban pop music for those with urban lifestyles”, music made for people on the go, who shuffle onto the subway as the sun comes down over Tokyo Bay, busy people with busy careers and even busier night lives and love lives. City pop promotes an “easy, breezy, top-down lifestyle” that is carefree, romantic, and punctuated by “lyrics about living the high life in the city.” It’s a music made for young, wealthy, downtown professional singles; once you get married and move out to the suburbs, you presumably won’t be able to listen to city pop any longer, as if it were recorded at a pitch that you’ve lost the ability to hear.

In the past five years or so, the internet has rediscovered the electric pleasures of the city pop sound, and fans have uploaded tons of songs, remixes, and playlists to YouTube. These videos are peppered with comments like these:

Imagine listening this at night at a Cafe or a bar in Tokyo in 1991… [sic]

Just imagining standing on top of building in Tokyo smoking a cigarette watching the sun setting and the office lights turn on one by one with the music playing somewhere off in the distance

You know, I used to always dislike those people that would comment things like “I was born in the wrong generation ughhh xdddd” but right now I can kind of understand that…imagine just sitting in a backstreet bar in Tokyo in the 70’s or 80’s drinking a cocktail and this is playing

The city pop vibe seems to inspire visions of living in the luxury of an affluent Cool Japan, where the sky is permanently at sunset and love is plastic. But folks on the internet have been obsessed with Japanese culture for a long time – why is it that city pop and its associated aesthetic mood is hitting it big right now?

City Pop and Today’s Political World

We could write off this interest in city pop and its Bubble Era lifestyle as typical otaku fantasizing, but I think that these fantasies are partly reactions to our current cultural and political climate. Fake news is all over the place, and people think that satire is real. Political discourse is beset by bad agents, and trolling isn’t just an impotent online exercise—it can lead to very literal, and very frightening, social change. We’re in a pretty deep hole and it isn’t clear how we’re going to get out of it.

The internet has made a lot of this worse. Let’s face it—the internet isn’t what we wanted it to be. It’s fulfilled the promise of being an information hub, sure, but it hasn’t exactly led to a utopian meeting of the minds. It’s a hotbed for violent groupthink and a training ground for extremist ideologies. Social media is a toxic dump and it’s difficult to know who or what to trust. Hell, this very post might have been written by a Russian bot.

The flashy, crisp, surface-deep world envisioned by city pop is an apolitical escape from this mess. Its anti-punk, high-production consumerist sound is about nothing but summer waves, sunset funk, and shy yuppie love, and it is a vacuum-sealed time capsule that keeps out any icky and uncomfortable economic or social realities. Much like disco, to which it has often been compared, city pop has no interest in politics, and it prizes dancing and romantic memories over activism or social change.

City pop insists that life is just one “endless, extravagant party” and you’re not supposed to think about big picture problems. You don’t need to worry about things like voting, racism, or worker’s rights. These problems might be out there, somewhere else, who knows—but they’re certainly not your problems. If you want to extricate yourself from the complicity of living in our complicated post-modern moment, city pop is an outlet eagerly designed just for that purpose.

Jason Morehead, writing for his blog Opus, candidly admits that he uses city pop as an escape from increasingly grim headlines:

Which just highlights what I ultimately love so much about “city pop,” that it seems to contain absolutely zero trace of irony and cynicism… and maybe it’s just all of the horrible things that fill the headlines right now — shootings, families being torn apart, deceptive and divisive politics — but I welcome any and all joy and optimism I can find these days.

Of course, there are many other ways to escape from these political and social issues: movies, video games, partying, etc. But I think that city pop is a particularly compelling form of escapism because it specifically plays on and addresses the anxieties that its listener might have about eschewing political and social responsibility. I’d like to hone in on two relationships that work together to make internet residents especially prone to city pop’s charms: the genre’s advertising-inspired art design and its intersection with anime.

City Pop and Commercial Style

City pop is a reassuring hand on your shoulder that says life is supposed to be fun and we shouldn’t waste so much time on ugly stuff. After all, it’s easier to move through a politically charged, ideologically savage cultural conversation if you convince yourself that none of this is about you and you don’t need to pay attention. It’s easier to live in a capitalist society when you can imagine that the capitalist world is your friend, not a breeding ground for data-gathering invasive predators.

In fact, if worrying about the failures of consumer life or about working conditions at Amazon warehouses gets you down, city pop is the ideal antidote. City pop is a world where buying products is great and no one had to suffer to sew your clothes or make your shoes or piece together your stereo. City pop was often multi-layered and crafted with delicate sonic complexity—it was played to best effect on fancy equipment, and it “sounded great in the kind of high-end automobiles Japanese consumers were buying” during the Bubble Era. The genre cultivated consumers with money, and it wanted them to feel good about having and spending that money.

To this end, city pop tapped into the fantasy energy of commercial and advertising art design; ads, like city pop, offer a version of life that is manicured, clean, and staged for our pleasure, an alternate reality that makes enjoying Coke or buying deodorant seem like the whole point of being on this planet. City pop and commercials are both polished and attractively sterile and built to sell you an idealized way of life. It’s no surprise that city pop music showed up in actual TV ads. City pop means never needing to think about the means of production, because we live inside the commercial for the product–life is one big ad.

Inspired by this connection, many fan-made city pop videos are backed by footage of commercials from the 80s and early 90s. Saint Pepsi, a DJ who samples from city pop records, has videos entirely made up of scenes from old Pepsi ads. Saint Pepsi is part of the future funk and vaporwave music movement, one of a number of Bandcamp DJs (among them Night Tempo and MACROSS 82-99) who sample from city pop records in sly quotes that play up city pop’s commercial sheen as a jab at corporate irresponsibility and tech bro bloat. But while there is plenty of irony to their use of city pop – one critic goes so far to claim that these DJs are a group of “sarcastic anti-capitalists revealing the lies and slippages of modern techno-culture”–I think that there is too much love and enthusiasm in their work for it to be overburdened with cultural commentary. I also think that city pop’s commercial attitude is so seductive and catchy that it bleaches out ironic asides.

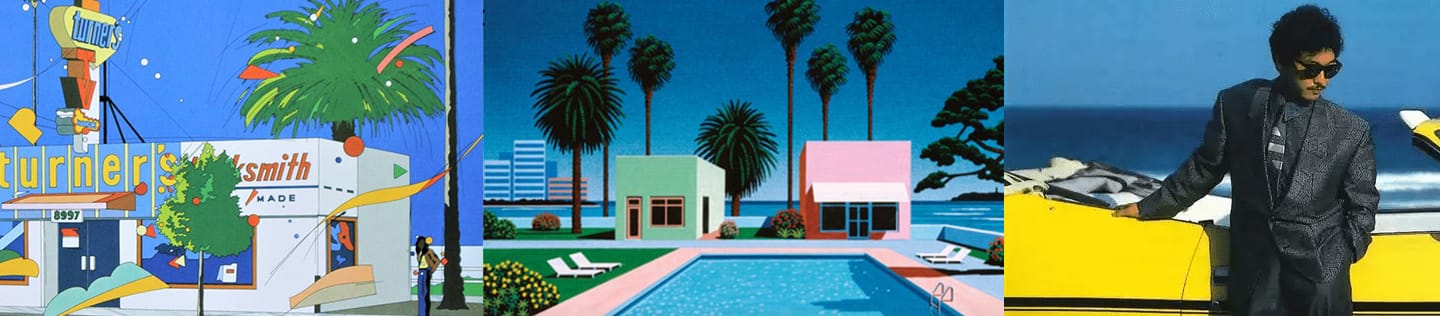

City pop especially cultivates this commercial attitude in its visual presentation; it’s a genre of music that was made for people who like to buy things, after all, so why not speak to them in their own language? City pop art direction often feels like it was produced more for magazine ads or high-end corporate flyers or hotel brochures than music album covers; it’s an aesthetic mode that Vice Magazine, in its profile on city pop, refers to as a “dreamy sense of billboard bliss”. City pop’s goal is to wrap you in the sort of bubbly embrace that you’d find in a great ad, placating you with the feeling that everything is going to be alright, as long as you’re willing to buy in.

This appeals to residents of the modern internet, because they are incessantly reminded that capitalism is a complete failure. Of course, this has been said for a long, long time, but the 2008 financial crash made it hard to ignore for even the most socially apathetic. The 2008 crash, like all big social shifts, has led to a healthy cottage industry in editorial think pieces, reminding us that corporations are not our friends and that we need to be vigilant for signs of the next economic disaster. The internet itself is culpable in the big economic problems we face today, and it may even have been constructed around this very purpose.

The internet, then, needs something like city pop: relaxing, soothing, tuned out of all that pesky negativity. City pop is a ticket to a time when it was okay to trust big companies and giving yourself over to consumer excess was a good thing. If drinking soda makes you feel complicit in an unhealthy corporate system, then just give up and come live in a soda commercial. The music will be great.

City Pop and Anime

The only thing that city pop videos enjoy showcasing more than old TV ads is old anime. Just about every other fan-uploaded city pop video is accompanied by scenes of Dragon Ball's Bulma bopping along on the beach or clips of City Hunter's cocktail-frosty neon skylines. These videos almost exclusively pluck moments from anime made in the 1980s, which isn’t too surprising—anime and city pop were two of the decade’s biggest Japanese pop culture highlights (and when these videos do highlight more modern characters, it’s usually someone like Spike Spiegel from Cowboy Bebop, who is a throwback figure).

But beyond just cultural proximity, I think that a lot of these old anime shows share a stylistic and thematic attitude with city pop that makes them a natural pair. Many of the decade’s big anime productions are glossy, flashy, and lavishly over-produced, financed with a level of Bubble Era money that we just don’t see today—or that, at least, rarely gets splashed out on direct-to-video animation about futuristic cities and giant robots.

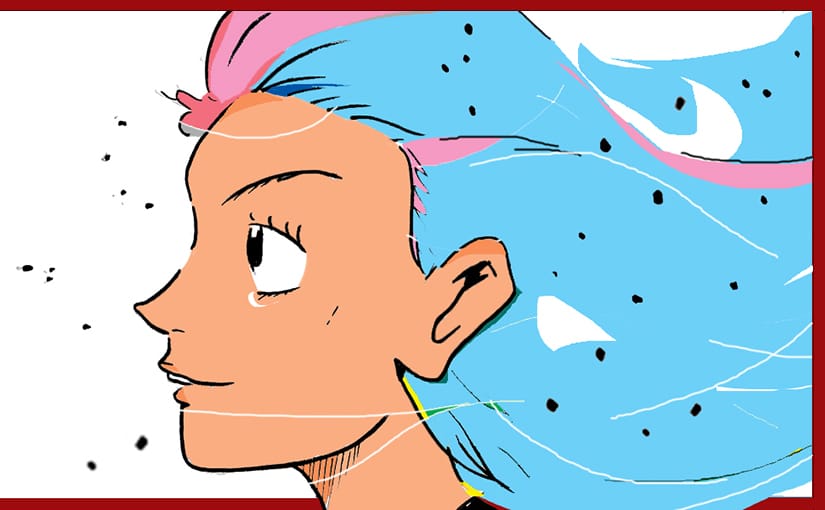

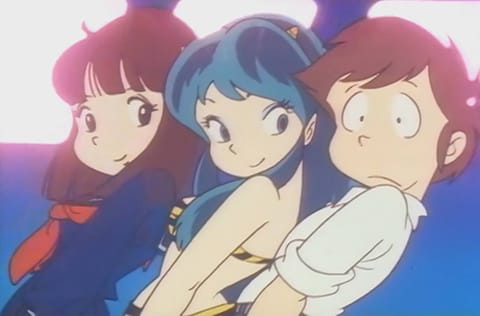

City pop’s echoes can especially be felt in anime romantic comedies like Miyuki or Maison Ikkoku, which are self-consciously nostalgic and wistfully bittersweet. Some of these romantic comedies, like Rumiko Takahashi’s sci-fi gag series Urusei Yatsura, are repeatedly featured in city pop playlists and remix videos; Lum, Urusei Yatsura‘s mischievous alien heroine, seems to have been elected as something of an unofficial city pop icon.

Urusei Yatsura might be so popular with city pop fans because the show’s surreal humor and effervescent romantic sensibility are so attuned to city pop’s wavelength—nothing is serious, everything is fun, and we’ll look back on all this with heady fondness. The series also has a peppy, irreverent art style that suggests we shouldn’t take anything here too deeply. In the end, whatever zaniness goes down, things will be okay and it’ll all be back to normal next week (Mamoru Oshii would use this vibe as the launching point for his arty movie based on the series, Urusei Yatsura: Beautiful Dreamer). The show’s city pop connection is further cemented by the fact that Cindy, a city pop idol, sings one of its ending themes.

Aside from anime’s easy ability to interface with city pop’s interests and goals, there’s also the fact that anime in general has become an internet shorthand language for escapism in its own right. It’s not a stretch to say that the internet views “escapism” and “anime” as nearly equivalent concepts.

The meme about internet fans holding out hope that American politicians will “make anime real” is tongue-in-cheek, of course, but it betrays a kernel of true desire. Anime itself has capitalized on that desire, as evidenced by the sheer number of recent projects about ordinary schmucks who find themselves transported to alternate worlds where they are powerful heroes and surrounded by beautiful girls.

Why do so many fans indulge in the fantasy that anime is real, or at least use it as an escape pod to break away from the real world? That’s a complicated question that is better left for a different article, but I think it’s for many of the same reasons that city pop is exciting for modern listeners: anime offers an unambiguous, thrilling version of reality where emotions are clear and well-defined, relationships are simple and obvious, and goals are sharply marked and attainable. If the real world is too confusing or alienating, anime is a comforting shelter from the storm. Hideaki Anno made a whole series about this very issue, reminding anime heads that they need to pull themselves out of the cartoon dimension and confront the necessary vicissitudes of real life.

In other words, anime is the ideal lubricant to grease the wheels for city pop’s revival. If city pop wants to draw the internet away from the troubled political reality around us, then anime has already done half the work. I don’t necessarily think that city pop fans were conscious of this natural interplay between anime and city pop when they went about making their playlist videos, but they clearly picked up on the connection and ran with it, whether or not they knew why it worked so well.

Looking Back

If we’ve begun to identify why city pop has so much purchase in today’s stressed-out, hostile internet environment, and if we’ve started to chart its relationship to the anime productions with which it is so often paired, there is still another part of the puzzle that we need to figure out.

Let’s go back to the comments that I quoted at the start of the article, written by modern city pop listeners who try to imagine what it would have been like to smoke a cigarette from the rooftop of an office building in Tokyo, the smooth vibes of Hiroshi Sato in their ear. The key idea in these comments—and in the thousands of similar comments posted on other city pop videos—is that the writers are “nostalgic” about the world that city pop evokes… even though, more often than not, they didn’t actually live in Japan during the 1980s.

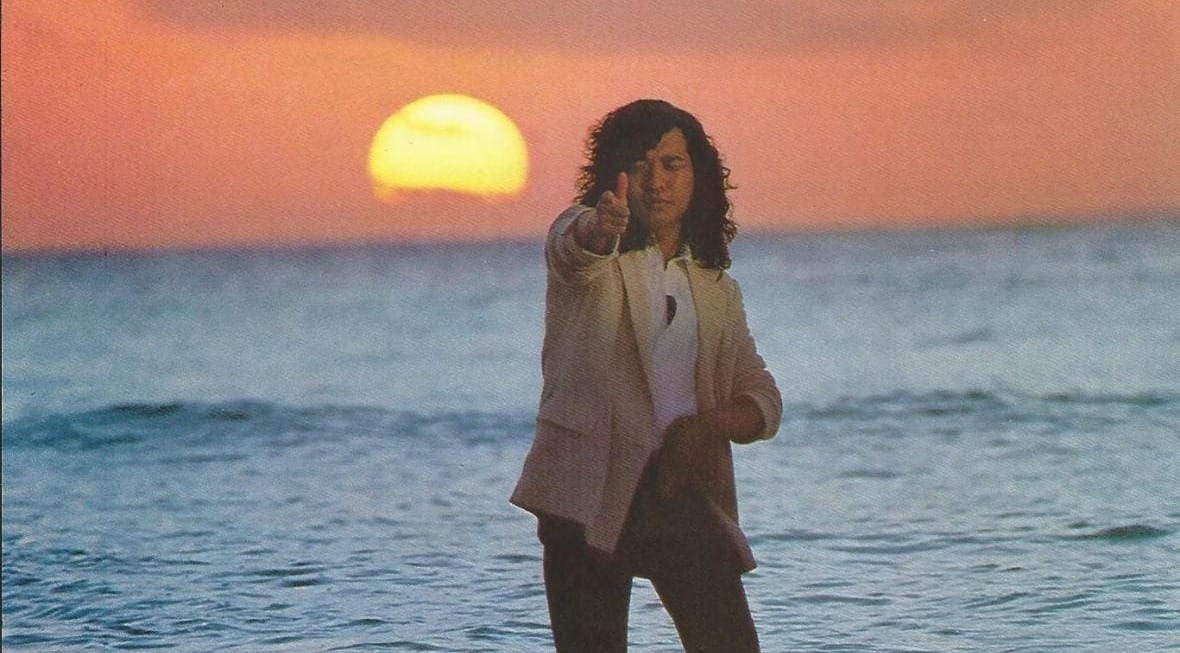

If you open up a particular upload of Tatsuro Yamashita’s bouncy city pop classic Ride on Time, you’ll find a comment that succinctly sums up this paradox (the comment also references Mariya Takeuchi, a city pop luminary and Yamashita’s wife): “Tatsuro and Mariya make me feel nostalgic for a life I’ve never had”. You’ll find this kind of comment on plenty of old music videos (“I’m only 13, but I love the Bee Gees…I wasn’t meant for this time, I wish I had grown up in the 70s!” and variations thereof), but the way that fans talk about city pop has a different register.

I think that what these comments really want to say is not that they are nostalgic for the past, but that they are nostalgic for a vision of the future that is locked away in the past.

Nostalgia for the Future

The Japanese Bubble Era didn’t last—the decline began in late 1989 and 1990, and then it quickly nosedived. The market couldn’t support all the rampant, hungry speculation that created the Bubble Era, and Japanese goods and real estate grew hideously overvalued. After the bubble finally burst, equity values “plunged 60% from late 1989 to August 1992” and this downturn was compounded by “toothless regulators who turned a blind eye to their losses”. This led to a period that is broadly known as the Lost Decade, even though it lasted much more than ten years; it was a time of extremely slow growth and general economic stagnation. Some economists think that Japan is still feeling these effects and a wide-scale recovery is nowhere in sight.

When the Bubble Era ended, city pop had nowhere to go. The rich people were drained dry and the nightclubs were closed. Conspicuous consumption was no longer in style, and Japan turned to rock ballads and bubblegum idol pop for musical salvation. These genres made people feel good and were outlets for escapism in their own way, but they didn’t have city pop’s vision and singular point-of-view. City pop was about more than just the music itself—like the commercials that it aligned itself with, city pop curated a fantasy way of life and an approach to thinking of yourself and the world around you.

No one thought that the Bubble Era would end, of course. It seemed like it could just go on forever, and the future would be all yachts and sports cars and designer sunglasses. City pop suggested that this would keep propelling into the future. It wasn’t a genre about staying static; it was about movement, upward mobility that had no ceiling, a future with “everyone on their way somewhere, the world full of promise.” We’d all be wealthy and carefree, living out our days on the beach and spending our nights in crystalline bars that looked out over hazy skylines.

Yes, we all could have spent the last thirty years living the neon high life, but the end of the Bubble Era nipped that life in the bud. When the bubble burst and the fizzy city pop fantasy evaporated, a possible future was closed off. When modern listeners say that they are nostalgic for the city pop era, they are mourning a future that never came to pass. They are looking back to see what could have been, longing for the chance to have been part of a future life that never existed. It’s a vision of the future that, as I said, is locked away in the past, a “backwards future” that is preserved in the city pop sound.

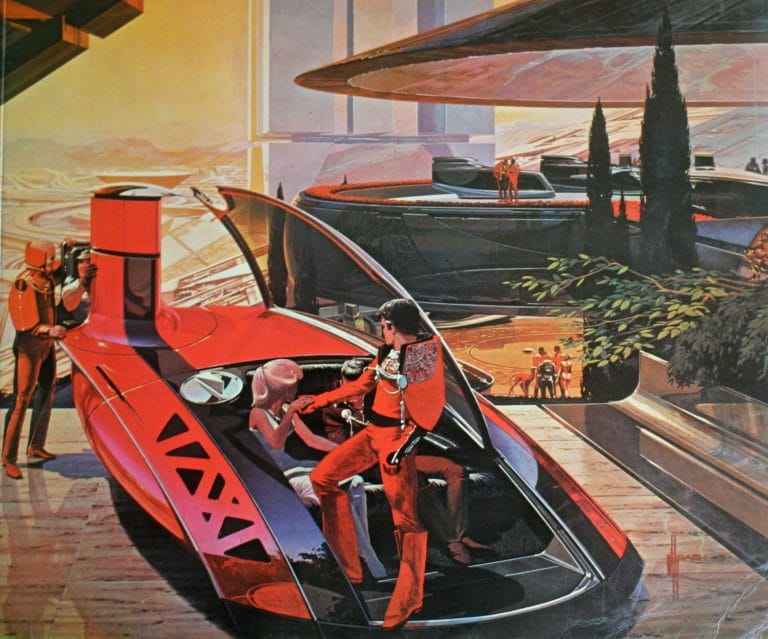

It’s not quite enough to call this retro-futurism. The appeal of the retro-futurist style (visions of the future inspired by what people in the ’50s and ’60s thought the future would look like, though there are some strains that draw on other eras) is that it is so quaint and pleasingly absurd. The jumpsuited jet-setters in retro-futurist art have very little relationship to our own world; they use outlandish technology that has no comparison to our own (hover cars, jetpacks, super-highways, and so on). It’s fun to look at and think about, but there’s very little suggestion that this is a future that we could have taken part in.

City pop’s future is more immediate and feels almost accessible, just barely within reach. Its future is more than a novelty—it’s a near miss. City pop is specifically unconcerned about the things that concern us today, and it directly addresses any anxieties that we have about troubling headlines: don’t worry about it and dance. Retro-futurism, by comparison, seems to about about people from another planet, who look like us but who are motivated by something that we haven’t yet evolved to consider.

Japanese visual artist F*Kaori, who is deeply inspired by both city pop and 80s anime, has some thoughtful things to say about the era’s appeal. She explains her passion for this aesthetic mode in an interview for Digital Arts magazine:

“In my opinion, it has a dreamy, fairy tale glamorousness to it. It’s the opposite of real. It reflects a desire to be immersed in a glam and kawaii [cute] world, to never leave a 1980s-based dream.”

In other words, city pop and its associated style is like a preserved air bubble that still contains a few breaths of rarefied oxygen from the 1980s; breathing in that air allows you to feel, if only for three or four minutes, like the city pop future is still just ahead. Listening to this music is like opening the door to a pocket dimension that still holds the promise of a bright, flashy future of consumer excess and creamy, pastel style.

Notes

- The comments I quote near the start of the article can be found in the videos for Mariya Takeuchi’s OH NO, OH YES! and Cindy’s Angel Touch, but you’ll find comments just like them on pretty much every single city pop video.

- As I mention, city pop video playlists prominently feature romantic comedies like Urusei Yatsura, but they also highlight several action anime. One action project that shows up in a lot of playlists is Megazone 23, which is a bit of a funny choice. On paper, Megazone 23 has all the hallmarks of a city pop poster child (including a huge Bubble Era budget): it is flashy, brilliantly animated, filled with fresh pop rock tunes, and even has a group exercise sequence featuring leotards and sweatbands. But the plot may cause you to do a double take, in light of what you’ve just read about the Bubble Era: Megazone 23 is about a glitzy, prosperous world that is revealed to actually be an elaborate illusion, where everything is controlled by a computer and no one is really free. Megazone 23 may be an emblematic product of the Bubble Era, but when seen in retrospect, it feels prophetic; the catastrophic end of the Bubble Era pulled back the curtain on all that prosperity to show that it was just a temporary illusion in its own right. The use of Megazone 23 in city pop playlists is ironic, but I’m going to guess that most uploaders only consider its sophisticated visual style and aren’t trying to make a tongue-in-cheek meta-statement.

- My personal favorite city pop singer (and probably the genre’s most famous figure) is Tatsuro Yamashita, who has a treasure trove of great tracks.

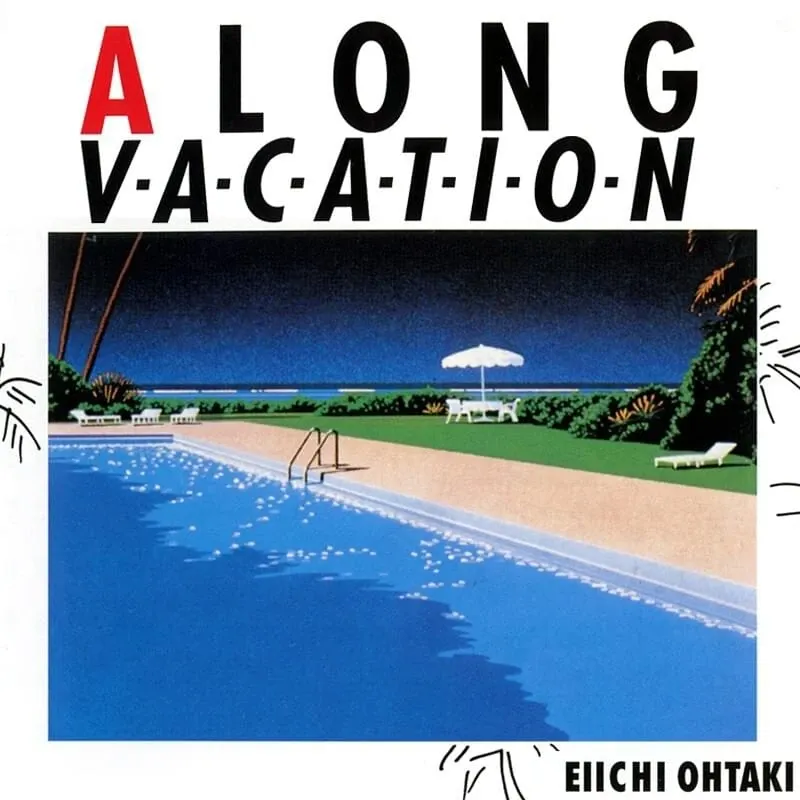

- Images used in this article, from the top: my own marker doodle, meant to capture something of both city pop flavor and 80s anime style; the cover of Momoko Kikuchi’s Adventure; the cover of Mariya Takeuchi’s single for the song “Sweetest Music”, which was used as the featured image for a popular upload of Takeuchi’s “Plastic Love”; album covers for Tatsuro Yamashita’s For You, Light in the Attic’s city pop compilation Pacific Breeze (art by storied city pop visualist Hiroshi Nagai), and Kiyotaka Sugiyama’s Sayanora no Ocean; Hiroshi Nagai’s cover for Eiichi Ohtaki’s A Long Vacation; a still from the opening credits of Urusei Yatsura; a much-distributed panel from the hentai manga Ne.To.Ge.; the cover of Tatsuro Yamashita’s single for the song “Ride on Time”; illustration by Syd Mead; and an illustration by F*Kaori.