The best retirement strategy for serial killers

If you don't mind committing murder, a tontine could be way more profitable than your 401(k)

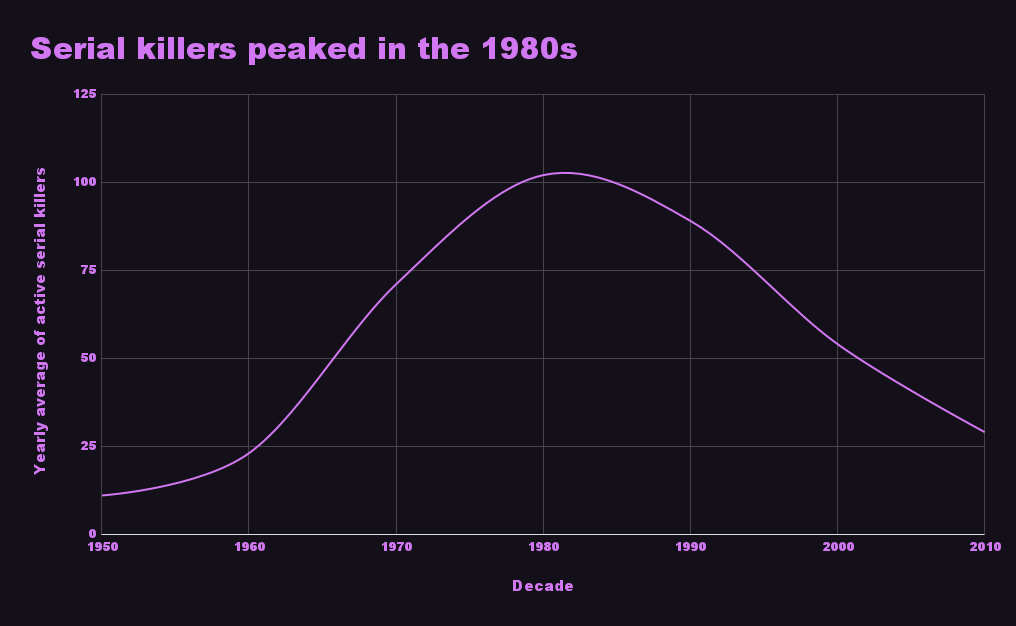

Maybe you’ve seen this horrifying fact floating around: the number of serial killers in the US has rapidly declined from its peak in the 1980s. Good news for people who don’t want to get murdered, but devastating for the true crime podcast and Lifetime original movie industries. There’s only so much content we can create about Jeffrey Dahmer—we need some fresh stories out there for the culture!

There’s one easy way we could boost the serial killer population: bring back tontines.

You might be familiar with tontines if you’re a scholar of 18th century public works projects or a fan of Agatha Christie. Here’s how they work: you and your friends all put some money into some type of fund. Every year, all of you get a payout from the tontine. It might not be a lot of money right now, but as your friends start dying (naturally or otherwise), your share of the pie increases. Once you’ve ensured that you’re the last one left, you’ll be raking in the dough. Sure, all your friends will be dead, but you can buy some new friends thanks to their life savings. Isn't that what they would've wanted?

Tontines have a long history dating back to the 1600s, and were quite popular for raising funds for everything from the Nine Years’ War to the first home of the New York Stock Exchange. Ironically, they were popular as life insurance policies in the late 1800s here in the United States. But abuses and scandals led lawmakers to heavily regulate them in New York state—and since most insurance companies were based in New York back then, it effectively created a national ban.

Tontines also have a long history in popular culture, ranging from the Miss Marple mystery 4.50 from Paddington to a 1996 episode of The Simpsons. What do these stories have in common? Attempted assassinations and mysterious murders.

Tontines “could be a super effective retirement vehicle,” said R. Tyler End, CEO of retirement planning startup Retirable, “if it weren’t for those damn serial killers and cold-blooded murderers.” Despite the risks, several experts and companies are attempting to revive the tontine. One of the biggest proponents is Moshe Milevsky, a finance professor at York University who has written several books imagining modern-day tontines. Unfortunately, he’s looking at it from the perspective of solving longevity risk—the chance you will outlive your savings—not from a desire to make the next Serial. In an interview with InvestmentNews, Milevsky tried to put the kibosh on the whole murder angle: “There is no documented evidence of anybody even being accused of murder to collect on a tontine other than in movies and fiction,” he said.

And yet, these new tontine products do a lot to protect members of tontines from each other. Tontine Trust, a fintech startup based in Miami that is trying to bring tontines back to America, say they’ll automatically assign and re-assign you to different pools depending on how their userbase changes. There’s not much point in killing anybody if there’s no guarantee you’ll be in the same pool as them forever. Savvly, another tontine-adjacent financial product, will actually return a portion of your initial investment to your estate if you die early. You’ll still need to keep a close eye on your heirs, but you should probably do that anyway.

Even if you’re not willing to stoop to murder, there is an element of the macabre inherent to taking part in a tontine—and despite that being a big reason why they fell out of favor in the first place, it’s also why people like them. Tontines aren’t that different from annuities, but annuities aren’t particularly common. One reason is that there’s a chance you’ll never profit. If you die the day—or even years—after you buy an annuity, the company just pockets your cash.

But with tontines, the equation is tweaked. That money doesn't just disappear—it gets redistributed. As writer Jeff Guo put it in a Washington Post article a few years back, “If people irrationally fear annuities because they seem like a gamble on one’s own life, history suggests that they irrationally loved tontines because they see tontines as a gamble on other people’s lives.” You might not be actively killing off other tontine members, but you’re still rooting for their deaths—or at least for your own relative longevity.

The more optimistic among us might say that widespread investment in tontines will encourage the general population to take better care of itself. We'll all eat vegan, hit the gym, quit drinking. We'll finally talk to a therapist about our constant paranoia that someone might murder us in our sleep. We'll be a fitter, happier America!

If you do end up investing in a tontine, let me know. I’m interesting in buying the exclusive audio rights to your eventual murder.