The fleeting frustrations of the diary writer

Confronting the passage of time, one entry at a time.

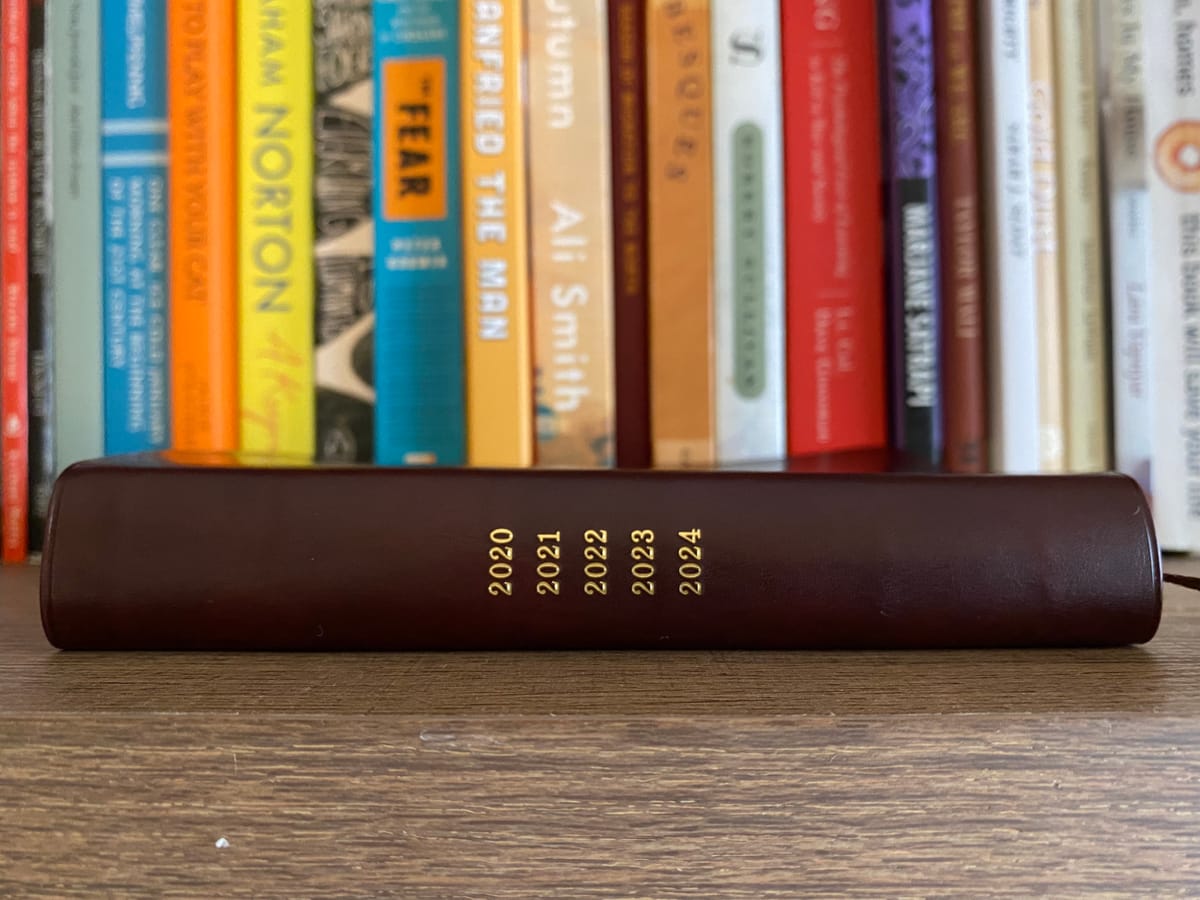

When I special-ordered a 5-year diary from Japan in December 2019, I didn’t realize how timely the purchase would be. Within a few months, I went from logging movie theater visits to global pandemic case counts, from writing about a great vegan restaurant to observing empty shelves at the supermarket, from tracking the ups and downs of the Democratic primary to an actual attempted insurrection.

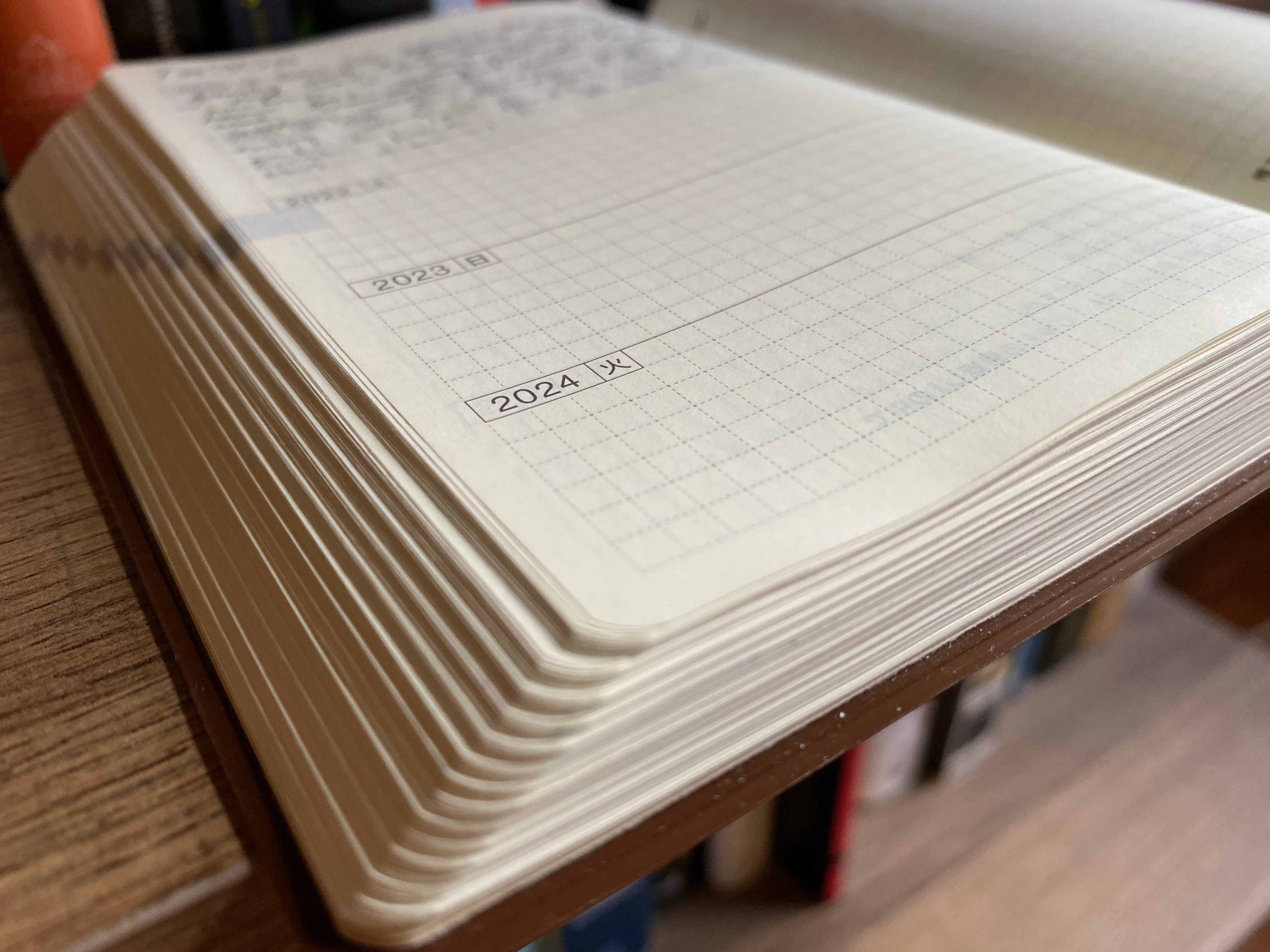

It’s one thing to understand, abstractly, that time passes, and another thing to confront it head-on for five to ten minutes every evening. But that’s exactly what writing in this little diary does. Just a bit shorter than your average paperback and thick like a bible, this diary has a page for every single day of the year, with five sections for five entries across five years. There’s not a lot of room for pontificating; the diary forces me to be concise and economical with what I choose to remember.

It’s a curious effect to see entries for different years side by side. Time feels compressed. The events in my diary feel both impossibly long ago and also like they happened yesterday. “What did we do a year ago today?” my fiancée frequently asks. We watched RuPaul’s Drag Race and ate take-out. I quit my job, then got a new one. Thousands of people died. I spilled tea on the rug. And I’m only halfway through year two! I can only imagine what it will feel like to see all five entries—five years of experience—together on a single page.

Almost ten years ago, in the Guardian, Joe Moran wrote in admiration of the diary writer. Diaries, he writes, can be historically significant, becoming “repositories of our collective memory,” but they are also “ruled by fleeting frustrations and passing piques,” the whims of eccentric writers who choose, unlike the vast majority of people, to write about what happened that day.

Take, for example, this teenaged diary entry, sent into the Guardian by reader Dinah Hall, from July 20, 1969: "I went to the arts centre (by myself!) in yellow cords and blouse. Ian was there but he didn't speak to me. Got rhyme put in my handbag from someone who's apparently got a crush on me. It's Nicholas I think. UGH. Man landed on moon."

Or this bit of my entry from January 21, 2020, the day the first COVID case was discovered in the US: “Good book club meeting. Bad book but good meeting and discussion. Went to Two Boots for a slice after even though we had vegan pie during meeting. Field Notes sent me a double of my order from last week so now I have a lot of red clicky pens.”

Life, like a diary, is fueled and defined by random whims and events as much as the larger forces. The Ians of the world don’t speak to the Dinahs, something massive happens that shapes all of our lives and defines our moment in history, and a warehouse manager accidentally sends two of the same order. It all takes up the same amount of space on the page.